[ The Herald ]

Cortez Kennedy spent most of his playing career as a dichotomy. Big, strong and quick as a whip on the field, he was often docile and relaxed off it. Mean and nasty between the trenches, Kennedy was more of a softy when the pads came off.

On the field, Kennedy was known for a quick first step that often put him in the opponents' backfield at about the time the ball was exchanged from center to quarterback. Off the field, Kennedy was known more for his infectious laugh -- a wheezing, guttural, heh-heh-heh chuckle that often included a stuck-out tongue.

Even Kennedy's playful side was a mask at times, hiding the pain that had bored its way into his soul over much of his adult life.

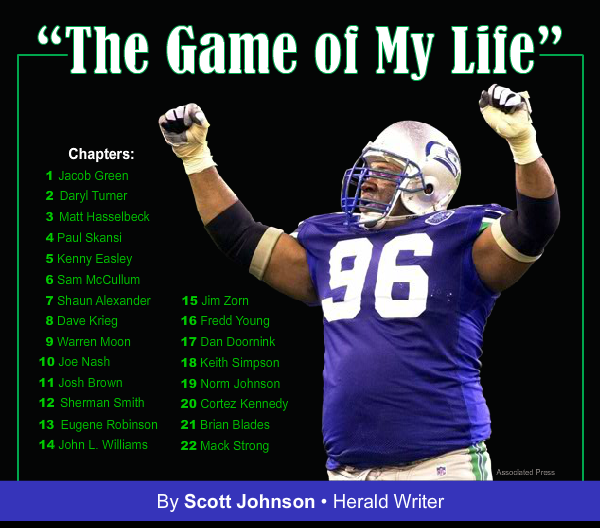

Cortez Kennedy was an enigma of sorts, but Seattle Seahawks fans will most remember him as a football player. His shy personality often led him from the spotlight, and so Kennedy did most of his talking with what he did on the field. Despite playing a position that rarely garners much attention, Kennedy did enough as a defensive tackle to make others take notice. He was an eight-time Pro Bowler, the 1992 NFL defensive player of the year and a semifinalist on the Hall of Fame ballot from 2008 to 2011.

As a football player, Cortez Kennedy was one thing. He was, quite simply, one of the game's best defensive linemen of the 1990s. And one of the greatest players to ever put on a Seahawks uniform.

Cortez Kennedy says he found the game of football for one simple reason.

"Where I grew up, in Wilson, Arkansas, there was nothing else to do," he said. "We used to throw rocks at each other for fun."

Kennedy chuckled as he said it, like he so often does. A massive, 300-plus-pound man, Kennedy puts people at ease with his laugh as quickly as he initially disarms them with his size. The cackling sound of Cortez Kennedy's pleasant chuckle often reminded teammates that football is, after all, a game.

Kennedy himself never had big goals as a football player. His dream in life was to follow his stepfather into the construction business or, at best, make it as a state trooper. Even when he started to shine at the sport during his days at Rivercrest High School, Kennedy was anchored down by subpar grades in the classroom. He ended up at Northwest Mississippi Community College, where he fully expected the playing days to quietly wind down to an oblivious conclusion.

But when an assistant coach from the mighty University of Miami football program came to NMCC to inquire about an offensive lineman with potential, the name of a player on the other side of the ball quickly came up in conversation. "Cortez Kennedy," the NMCC coach told Miami assistant Tommy Tuberville in 1986, "that's who you want to see."

At 6-foot-3 and 306 pounds, Kennedy moved like Baryshnikov while packing the punch of Tyson. His reputation preceded him at Miami, where there was so much talk about Kennedy's arrival that even some of the school's most famous football alumni had to stop by to get a look at him. Jerome Brown, a former All-American who was in his rookie year with the NFL's Philadelphia Eagles, was among the players who sought out Kennedy right away.

"I was in the weight room lifting, when this guy comes busting through the doors saying, 'Which one's this fat kid who's supposed to be like me?'" Kennedy recalled in 2008, chuckling as he spoke. "Then he introduced himself and gave me a hug. He said, 'Keep up the good work.'"

It wasn't long before Brown and Kennedy were close friends. After Kennedy turned in an All-America career of his own at Miami, he took on Brown's agent, a man named Robert Fraley. Much like Brown had three years earlier, Kennedy entered the NFL draft as one of the most sought-after players in the country. The Seattle Seahawks traded their two first-round choices to move up in the draft and select him with the third overall pick.

Kennedy didn't quite ingratiate himself to his new city upon his 1990 arrival, which was delayed by a contract holdout. The rookie started just two games that year but began to get a feel for the NFL as the season went along.

"By the end of my rookie year, I knew I was playing good," he recalled. "I was just figuring out what I needed to do to be a pro."

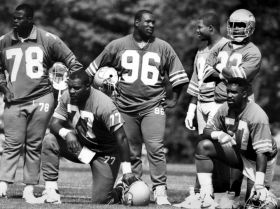

Playing on a team that had plenty of established veterans on defense, Kennedy tried to learn all he could from players like Jacob Green, Jeff Bryant, Eugene Robinson and, most notably, Joe Nash.

"He really took me under his wing," Kennedy recalled.

By the second season of Kennedy's career, he was in the starting lineup and making quite a name for himself. He had six sacks in the first six games of that 1991 season before suffering a knee injury that limited him at practices over the final two months of the season. Kennedy finished the season with 6½ sacks and 67 tackles – both uncharacteristically high numbers for an interior lineman. For his efforts, he was named an alternate to the Pro Bowl. And when another AFC defensive tackle backed out of the annual all-star game, Kennedy was on his way to Hawaii.

The first person he called was Brown.

"He said, 'You didn't earn it,'" Kennedy recalled of his old U. of Miami friend's reaction. "That really pissed me off. I couldn't believe he'd say something like that.

"But what he meant was: you didn't get voted in. When I saw him in Hawaii, he said, 'You're going to make it on your own one day.'"

Four months later, Jerome Brown was gone. In June of that year, Kennedy had plans to travel to Florida with his longtime friend. Brown and Kennedy had a phone conversation to finalize the details of their travel plans, and a few minutes later Kennedy called Brown back. But he did not answer. Kennedy called again and a roommate picked up, saying that Brown had gone to the bank.

Two hours later, Kennedy's phone rang. Seahawks PR director Dave Neubert was on the other end to deliver some sad news. He had just heard that Jerome Brown was dead.

"That's impossible," Kennedy said. "I just talked to him on the phone."

During Brown's run to the bank, he crashed his Chevrolet Corvette and died at the scene, along with his nephew. Brown was 27 years old.

"Mentally, it messed with me because I never had lost a friend like that, a person I cared about like that," Kennedy said in 2008.

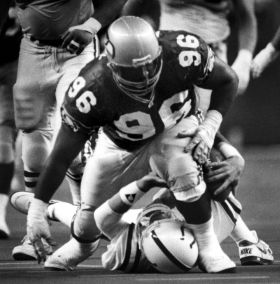

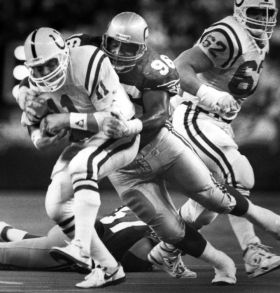

In the fall of 1992, Kennedy temporarily changed his jersey number from 96 to 99 in honor of Brown. And not only did he have a Pro Bowl year, but the kid from Wilson, Ark., had what may well be the finest season of any defensive player to ever wear a Seahawks uniform. Despite playing for a 2-14 team, Kennedy was a unanimous selection as the NFL's Defensive Player of the Year. With 14 sacks and 28 tackles for loss, Kennedy dominated the league and led a defense that got very little help from the guys on the other side of the ball.

During that 1992 season, Kennedy's finest game came in a rare win. The 0-2 Seahawks went to New England trying to rebound from a pair of lopsided losses. Thanks to Kennedy, Seattle would come away with its first victory of the season.

Seahawks vs. New England PatriotsSeptember 20, 1992

as told by Cortez KennedyAs a team, that wasn't our best year. We got beat pretty bad in our first two games, so we knew we had to get it together if we were going to win any games all season.

We had a pretty good defense that year, but we couldn't put any points on the board. Our defensive coordinator, Tom Catlin, won assistant coach of the year that season even though we were a 2-14 team, so that says a lot. Our defense was great, but we didn't have much going on over there on the other side. I didn't worry too much about the offensive struggles. I just looked at it like: I can't control what's on the other side of the ball; let's just not embarrass ourselves on defense. I took everything for what it was. The guys who could play, they played. The guys who couldn't, it's not my job to talk about what they could or couldn't do. It's not like the other guys weren't trying. We were all trying out there. I just did my job and tried to take care of what we could do on my side of the ball.

We were a really good defense that year. When I came in, we already had great leaders in Eugene Robinson and Jacob Green and Joe Nash, guys like that.

So in that game, against New England, we really wanted to play our best as a defense to give us a chance to win. It was at New England, but it was a pretty warm day. I remember I was lining up against a guy named Eugene Chung, a guard, for most of the game. We were lining up one-on-one early on, but they had to start double-teaming eventually. I had three sacks in the first half alone.

I remember early in the game, maybe in the first quarter, I sacked the Patriots' quarterback, Hugh Millen, on a screen pass. That's amazing. You never see that. Our linebacker, Dave Wyman, called out for me to go left. As soon as the ball was snapped, I went left. The center was trying to hold me, but I got through. I got back in the backfield so quick. That's almost impossible, to sack a quarterback on a screen.

Some of the stuff I did, I just did alone. Other times, I was getting sacks because we had a lot of pressure in the backfield. I ended up with the three sacks, two forced fumbles and five tackles for loss. When you're on, you're on. When you're off, you're off; but sometimes you're on, and you just have one of those games.

At one point, I tried to rush from the left side, where Jacob Green lined up at defensive end. He said, 'Get your butt back on your side. Don't be taking away any of our sacks over here.'

I sacked their quarterback two more times and made a bunch of plays in the backfield. That was my thing: tackling guys before they got back to the line of scrimmage. That year, I also broke the Seahawks record for tackles for loss, with 28. When I went on to work for the New Orleans Saints at training camp a few years later, I would tell my linemen: 'Don't wait for the runner to get to the line; try to get them in the backfield.' I didn't always make the plays in the backfield, but I tried.

I ended up having a great year that year. I had 14 sacks, and eventually teams started double-teaming me. I didn't realize how good I had it until they started doubling me every play. I remember playing up in Denver, and their tight end, Shannon Sharpe, said: 'You're not going to beat us today. We're going to double-team you and make someone else do it.' And that's what they did.

While the Seahawks won only one more game all season, Kennedy went on to become the second Seahawk to be named the NFL's Defensive Player of the Year. He said he wasn't surprised by the award, only that he was a unanimous choice.

After hearing that he'd been named the league's top defensive player, Kennedy called one of his closest friends in the NFL, Kansas City linebacker Derrick Thomas. The Chiefs' Pro Bowler had 14½ sacks that season, putting up the kind of statistics that were worthy of a trophy.

"When he picked up (the phone), he said he was going to win the player of the year," Kennedy recalled. "I told him, 'Man, I already got it.'"

Thomas and Kennedy continued to grow closer over the years, but like too many of Kennedy's relationships, that one eventually ended in tragedy. It was a routine of morbidity that would define Kennedy's adult life.

In 1999, when Kennedy's career with the Seahawks was winding down, his season was abruptly interrupted by news that agent Robert Fraley died in an October plane crash. Fraley, 46, was on the same Learjet 35 that went down with professional golfer Payne Stewart aboard.

"I always wanted to be like Robert," Kennedy said in 2008. "I looked up to him. He was always the same; he never got upset. When he passed away, a part of me seemed like it passed with him."

During the next day of team meetings, Kennedy was unable to distract his mind. The massive, light-hearted man broke down in tears in front of his teammates and coaches. Seahawks coach Mike Holmgren gave Kennedy the rest of the day off, telling him to go home and properly mourn. A few days later, with a heavy heart, Kennedy took the field for a Monday night game at Green Bay. Kennedy played one of the greatest games of his life, sacking Packers quarterback Brett Favre twice and backup Matt Hasselbeck once. After the game, Kennedy got a call from longtime NFL coach Dan Reeves, another of Fraley's clients.

"Robert would have been proud of you," Reeves told Kennedy.

Three months after Fraley's death, tragedy struck again – the third time in eight years that one of Kennedy's close friends was involved in a tragic accident. While traveling to attend a playoff game as a spectator, Derrick Thomas got into an automobile accident that left him paralyzed in January 2000. Thomas called Kennedy often from the hospital.

"Derrick was one of those people who always kept it short when he talked to you," Kennedy recalled. "But he couldn't go anywhere because he was paralyzed, so you couldn't get him off the phone. We talked for two hours before the Pro Bowl. We were talking about life, about football, about how hard it was for him to be missing the Pro Bowl."

On Feb. 8, 2000, a few weeks after the crash, Thomas suffered a heart attack at the hospital and died at the age of 33.

That year would mark the final Pro Bowl for Kennedy, who played in the annual all-star game every time he was invited. He struggled through a 2000 season while showing signs of age, and after the Seahawks stumbled to a disappointing 6-10 record Kennedy quietly announced that it was time for him to move on. There was no ceremony, nor a press release to commemorate the event. After a couple of tryouts with other teams, Kennedy opted for retirement. In the end, he played for only one NFL team.

"I didn't want to leave Seattle," he recalled in 2008. "The fans there were great. They treated me with the utmost respect. I didn't care about the media attention, I tried to conduct myself off the field like a gentleman, and I tried to do the right thing on the football field. And I think they appreciated that."

In 2006, Kennedy became the 10th member of the Seahawks' Ring of Honor. The following year, he was honored for his 11-year career by being named one of the semifinalists for Hall of Fame consideration. Upon hearing that his name was on the list, Kennedy made a phone call to longtime friend Mickey Loomis, a former member of the Seahawks' front office.

"Hey, Mickey," Kennedy said, "was I really that good?"

When he recalls the story, Kennedy lets out that good-natured chuckle. It's an infection, one that nobody can avoid. No matter how much heartache Kennedy has endured, he still has that ability to exude happiness – for himself and to those around him.

That, even more than anything he did on the football field, was Cortez Kennedy's legacy.