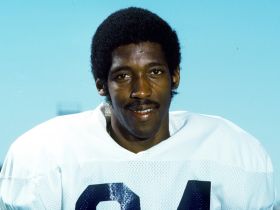

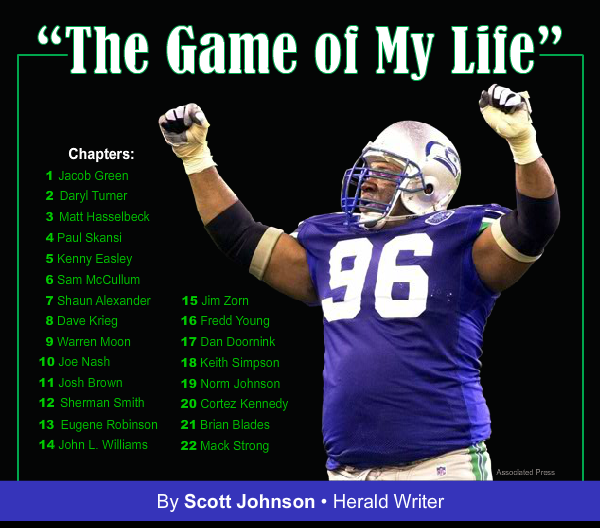

[ Seattle Seahawks ]

The greatest game of Sam McCullum's six-year career in Seattle wasn't a memorable, come-from-behind victory that changed the course of a season. In fact, it wasn't even a victory. And to call it memorable would actually be misleading because McCullum doesn't remember a thing that happened after halftime.

After suffering a concussion at the hands of a man that many consider the hardest hitter in NFL history, McCullum blacked out but still set a franchise record for receiving yards in the game.

It marked one of many highlights of a Seahawks career that was sandwiched between McCullum's two stints with the Minnesota Vikings. While he left the Vikings in 1976 to become a founding member of Seattle's first NFL team, McCullum eventually saw his Seahawks career end on bad terms.

The outspoken McCullum got along with plenty of teammates along the way, but he also butted heads with some people, and even fell out of favor with one head coach. And yet one man with whom he never had any issues was the hard-hitting defensive back who temporarily knocked him silly and erased McCullum's record-breaking performance from memory.

In a sense, Sam McCullum's childhood prepared him for a football career that was constantly evolving. The son of a military man, McCullum lived in eight different states before he even started attending high school. The constant moving was hard on McCullum, who had to reinvent himself every couple of years in front of a new group of peers.

"You don't get attached to things too quickly," McCullum said of his upbringing. "You just get up and go and adjust to what's in front of you. It can be a good thing and a bad thing."

As an African-American, he experienced what he called "blatant" racism in southern states like Mississippi, while feeling something like a "novelty" in mostly white areas like Kalispell, Montana, and Ferndale, Washington. He never really felt like he fit in, until he started playing sports.

Athletics were among the few constants in McCullum's life. He started running track as a fifth-grader in Ferndale, went out for the basketball team as a sophomore in high school, and took up football as a junior at Kalispell's Flathead High.

"Sports helped a lot," McCullum said. "I might have been going out and getting into trouble, but instead I was spending all my free time running track or playing other sports. It was a way to get past some of (the issues of fitting in)."

While McCullum's life gained some stability in high school – his father, Mac, retired and kept the family there for Sam's final two years at Flathead – his affair with football was not a love-at-first sight proposition. The high school coach started him out as a linebacker, only to see McCullum's stint on defense last exactly one practice. Thanks to a broken hand that McCullum suffered getting his fingers caught in a teammate's helmet, his junior season got cut short. He only played in two games, both at tight end, before switching to the somewhat safer position of wide receiver as a senior. It was there that the speedy track star really excelled. He eventually earned a scholarship to Montana State in Bozeman, where he would go on to break a school record by scoring 16 career touchdowns. Twelve of those came in McCullum's junior year, including two in a game against rival Montana to help end a three-year losing streak to the rival Grizzlies.

In 1974, McCullum became the first MSU wide receiver ever selected in the annual NFL draft. The Minnesota Vikings took him in the ninth round and immediately started using him as a return man. He also saw some time as a backup receiver late in the year, including a memorable regular-season finale in which he took such a punishing hit from Kansas City linebacker Willie Lanier that left McCullum looking through the earhole of his helmet. McCullum caught two touchdown passes in that game, and his Vikings went on to play in Super Bowl IX before losing to Pittsburgh.

McCullum felt poised for a breakout year in 1975, when he went to training camp as a starter following veteran John Gilliam's defection to the World Football League. But McCullum separated his shoulder in the preseason finale, the Vikings lured Gilliam back from the WFL, and McCullum caught just two passes in nine games that season.

The Vikings' decision to leave him unprotected in the 1976 expansion draft greeted McCullum with mixed feelings. On the one hand, McCullum was familiar with the Vikings and knew they would be a Super Bowl contender. But he didn't like playing in the Minnesota cold, and McCullum also looked forward to the opportunity to get a fresh start and compete for a chance to be the go-to receiver.

The Seahawks selected McCullum in the expansion draft, and he soon showed up for a training camp unlike any other he had ever seen. More than 300 players practiced with the team during the six-week camp, and things got so confusing that everyone's helmet had to include a piece with his name written upon it.

"We had so many new people coming through, it was incredible," McCullum later recalled.

Naturally, McCullum kept an eye on some of the other receivers at camp. He developed a quick rivalry with a young veteran named Ahmad Rashad, who would never play for the Seahawks but would eventually be reunited with McCullum in Minnesota a few years later. The pair never got along, for whatever reason, and McCullum didn't think much of Rashad's skills during that first camp.

"I was unimpressed," McCullum said in 2007. "I was competing against him for my job, and I did well enough that they eventually traded him."

The rotating roster continued right up until the week before the inaugural opener, when the team added eight more players. One of those was a young receiver named Steve Largent, who was acquired from the Houston Oilers and eventually joined McCullum in the starting lineup.

Much like McCullum's childhood as the son of a military man, the first few years of the Seahawks' organization were in a constant state of flux.

"They kept changing the roster every year," McCullum said. "It was amazing how many people we went through year after year. We had so many new players that it took time for us to figure it out, and it took us a while to play well."

McCullum was one of the few constants, becoming an immediate starter. Meanwhile, the Seahawks were a typical expansion team in that they struggled in their first two years before starting to see some success. He scored the lone touchdown in the first victory in franchise history, a 13-10 victory over fellow expansion team Tampa Bay in Week 6, then missed most of the 5-9 season the following year because of injuries.

By 1978, McCullum was having a breakout year, and the Seahawks were looking like legitimate playoff contenders. He caught 37 passes that season, which was a career high at the time. Largent, meanwhile, continued to be the Seahawks' go-to receiver on his way to a Hall of Fame career.

McCullum said he maintained a kinship with Largent but never considered him a close friend until after their playing careers were over. McCullum claimed that their initial distance had less to do with religion – Largent was open with his Christianity, while McCullum converted to Judaism as an adult – but with other "differences" in their personalities.

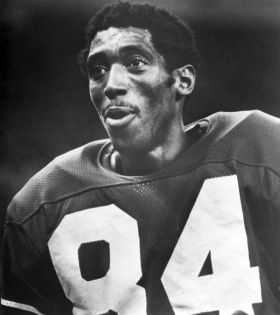

The 1978 season saw the Seahawks go 9-7, with a pair of wins against the mighty Oakland Raiders. In those games, McCullum faced off against a 30-year-old safety who had already become legendary for his big hits.

Jack Tatum was every receiver's nightmare. The Raiders' defensive back had already been to three Pro Bowls, and he was considered by many to be the best hitter in the game. During the 1978 preseason, he made his most notorious hit when he left New England Patriots receiver Darryl Stingley paralyzed. The controversial hit led to questions about whether Tatum was a dirty player. Fans, media and opponents wondered aloud if he was being too aggressive for his own good.

McCullum knew about Tatum's reputation but never considered him to be dirty. He did make sure to know where he was on the field any time the Seahawks played the Raiders, and yet in the most productive game of McCullum's Seattle career, during a December 1979 game against the Raiders, he left himself exposed.

And McCullum paid for it.

Seahawks vs. Oakland RaidersDecember 16, 1979

as told by Sam McCullumI set the franchise record for the amount of receiving yards in a game, 173, although it didn't last very long -- less than five years. The game sticks out because Jack Tatum hit me so hard that he made me dizzy. He gave me a concussion late in the first half, and I came back and played in the second half. I don't even remember the game after that.

In the early parts of the game, I had a fumble, which really upset me. I caught a pass and was going in for a touchdown, and I fumbled on the 5-yard line. I remember that.

Then afterward, I made a great diving catch, and then Jack Tatum hit me. He came over and made a big hit. I don't remember anything after that, but I remember the hit. I was running a crossing route. It didn't look like it was a hard hit, but he was just so strong. I went over the middle, laid out for the ball, caught it, and he knocked the crap out of me.

I was surprised that quarterback Jim Zorn threw me the ball. If I had just kept running, I probably would have run right into Jack Tatum's face. But as it was, Zorn threw the ball and I went and dove for it. So I went out and got it. And I made the catch.

It happened late in the first half, and I don't even remember what happened in the third quarter. Those were the days when they gave you some smelling salt and ice water and put you back on the field. In this day and age, they'd probably send you to the locker room and put you under the microscope and tell you you couldn't play for the next month. It's changed a lot.

Tatum was such a hard hitter, but he was never a dirty player. He never talked. The Raiders' other star defensive back, Lester Hayes, never shut up, but Jack Tatum never talked. I can't remember him ever, ever saying anything to anybody. But you knew exactly where he was at because he was such a big hitter. He was a small guy, about 5-11, but he was built like a solid brick. He could really hit you. He didn't do anything dirty; he was just that strong. It was amazing. You wanted to play him one-on-one because he couldn't cover. But if he was out there in space, he would get you.

I caught three more passes in the second half, but don't even remember that. I didn't even know that I had set the franchise record for receiving yards until after the game. One of the reporters told me. It felt good, but then again we lost the game. I would have taken the win over the record. You just move on. You come home, you're sore, and you lost the game. Yeah, I got the record, but we still lost.

When the game finally ended, I didn't remember the yardage because we lost the game. It wasn't something I looked at until later on. It didn't matter because we lost. I really wanted to beat the Raiders, and it didn't happen.

Similar to McCullum's childhood and early career in Seattle, the Seahawks continued to be in a state of evolution, nipping and tucking their roster until it finally caught up with them. After successful seasons in 1978 and '79, the team struggled to a 4-12 record in 1980. McCullum had a career-best 62 receptions that season, just four fewer than Largent. The following year, 1981, was more of the same in terms of wins and losses. Seattle finished at the bottom of the five-team AFC West for the second year in a row, with a 6-10 mark. That 1981 season was significant for another reason as well. McCullum's teammates chose him to be the player representative, and although he would later say that he thought that title might affect his standing with the coaches, he accepted.

"The players asked me to step up," he recalled. "But I was concerned about it because I heard that if you're a player rep, you'll get cut. (Seahawks coach) Jack Patera and I were very, very close from our days in Minnesota together. I thought I'd be safe in that environment. But it was very dangerous, and I knew that."

Not one to sit back and let things happen around him, McCullum took an aggressive approach to the new title. He spoke up for the players' union, questioned medical procedures and encouraged pre-game handshakes with opposing players as a symbol of union solidarity.

In 1982, with a players strike on the horizon, McCullum's status on the team became tenuous for the first time. Patera began fining players who participated in the solidarity handshakes, and his relationship with McCullum had become strained. Two weeks before the 1982 season was scheduled to begin, McCullum was released. Shortly thereafter, Patera defended the move by saying that McCullum was not released because of his union ties.

"I'm not saying McCullum was a bad football player," Patera was quoted as saying on a Seattle radio station. "He was the (team) MVP one year (in 1980), and that year was our worst record. So he was the best when we were the worst.

"I think Sam is a very selfish football player; he always wanted a lot of passes thrown to him."

The release and ensuing comments did not sit well with McCullum, whose wife was pregnant with the couple's second child. While he eventually landed on his feet by returning to the Vikings a week later – he caught 12 passes during the strike-shortened, nine-game season – McCullum immediately filed a grievance against the Seahawks. The case eventually went all the way to the Supreme Court, and in 1995 -- 11 years after the conclusion of his NFL career -- McCullum won a suit that awarded him an undisclosed sum of money under the Unfair Labor Practice laws.

McCullum ended up playing 10 seasons in the NFL – six with the Seahawks, sandwiched between four with the Vikings. He went into business after his football career was over, doing everything from politics to his most recent job as vice president of a bottled water company called Advanced H2O. He doesn't regret his union ties, pointing out that his lawsuit helped open the door for several other labor-law cases over the years.

McCullum retired to the Seattle area and recently said that his problems with the Seahawks are a thing of the past.

"That was patched up a long time ago," he said in 2007. "When Paul Allen took over the team, it all changed. When Ken Behring owned the team (from 1988 through 1996), it was very ugly. It was not a good time for the players."

But the unkind side of football still lingers for McCullum. He suffers from osteoarthritis in his knees, a condition that prevents him from doing much physical exercise. While he can ride a bike, swim and play golf, McCullum can no longer run or walk long distances.

That did not stop him from passing on the game to his two sons. Jamien and Justin McCullum both played football at Stanford, and Dad never got in their way.

"I was hoping they'd play other sports," he said in 2007, "but I was never the kind of dad who was going to push them one way or the other. I just never did, and sometimes I think they wish that I had.

"If they wanted to do something, whatever it was, I wasn't going to push their decision one way or the other."

And as for the former opponent who delivered the hardest hit McCullum had ever withstood? Jack Tatum eventually went to three Pro Bowls, and the man known as The Assassin is still considered one of the toughest guys to ever play the game.

Hall of Fame safety Ronnie Lott once called Tatum "my idol."

Tatum himself was once famously quoted as saying: "I like to believe that my best hits border on felonious assault."

Sadly, the most notable victim of a Tatum hit never recovered. Darryl Stingley died in 2007, living the final 29 years of his life as a paraplegic. Tatum never visited Stingley in the hospital or personally apologized for what happened to the former Patriots receiver in 1978.

"I'm not going to beg forgiveness,'' Tatum said in a 2003 interview with a New Jersey newspaper, around the 25th anniversary of the hit. "That's what people say: You never apologized. I didn't apologize for the play. That was football. I was sorry that he got hurt. Even today, people still think I'm a bad guy.''

That same year, Stingley admitted that Tatum had tried to set up a televised apology but that he did not want to accept it unless the act was done in private.

"If they showed up at my door without a camera, then we could have some real healing," Stingley told the Boston Globe in 2003. "This is a world built on hype. Selling newspapers. TV ratings. Those are real. But in my world what's important is to have a forgiving nature."

McCullum feels fortunate that his 1979 run-in with Tatum left no lingering damage. He also believes that Tatum should not be blamed for what happened to Stingley.

"I didn't think it was a dirty hit," said McCullum, who only saw the hit on Stingley through television replays. "He didn't try to hurt anyone; he just tried to play defense. It was not a dirty hit. I saw it (on television), just like everybody else did.

"Darryl was the first guy to be hurt like that, so as a receiver, you always worried about it after that. But I never saw anything that told me it was a dirty play."

Nor did McCullum believe that Tatum's 1979 hit in a Seahawks-Raiders game was dirty. It certainly hurt, but it didn't keep McCullum from having his most memorable game in a Seattle uniform.