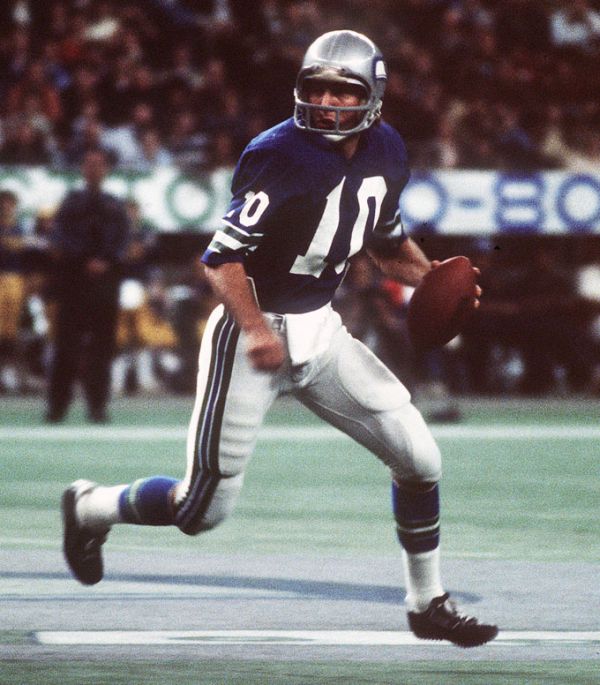

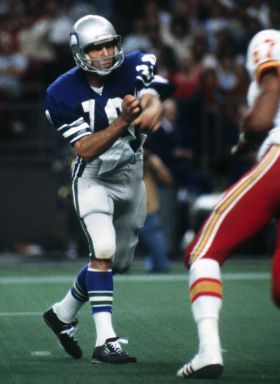

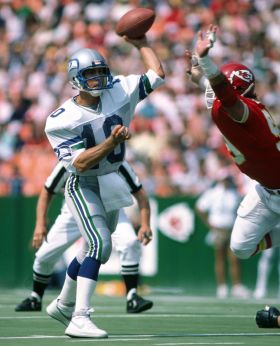

When the Seattle Seahawks signed unknown quarterback Jim Zorn off the street, they had no way of knowing that he would eventually be the franchise's first star player. And their low expectations didn't change much when they saw him in person for the first time. Nothing about Zorn was typical of an NFL quarterback. He had a strange name, a floppy haircut and he threw with his left arm. He played college ball at Cal Poly Pomona, not exactly a football powerhouse, and had already been cut by the Dallas Cowboys. And as for his style of play? Let's just say that Zorn was the antithesis of the polished, dropback passer that would soon become all the rage.

But the more the Seahawks watched Jim Zorn run around during that 1976 inaugural season, the more they saw shades of renegades like Terry Bradshaw, Fran Tarkenton and Ken Stabler. And the more they realized that he was the guy to carry the new franchise into its first season of NFL play. And so the Seahawks built an offense around the unorthodox Zorn, and he brought excitement to Seattle from the very start.

"We had excellent success at the box office everywhere we'd go," said John Thompson, the team's first general manager. "He didn't have the glamor of Joe Namath, but the team was exciting. I still hear it now, however many years later, people refer to the Zorn-Largent days as the most exciting days in team history."

By the end of Zorn's career as a Seahawk, he was often remembered as the guy who lost his starting job to Dave Krieg during the franchise's memorable, unexpected 1983 season. But ask anyone who witnessed the first few years of Seahawks football, and the words "Zorn" and "exciting" are guaranteed to come up at some point in the conversation.

Before Krieg and Matt Hasselbeck, Curt Warner and Shaun Alexander, Kenny Easley and Cortez Kennedy, and even before future Hall of Famer Steve Largent came along, there was Jim Zorn.

The Seahawks' original star.

Jim Zorn can still name all the players who preceded him as Seattle Seahawks. There was Dave Williams, a wide receiver from the University of Washington. There was Bob Cason, a quarterback from the University of Puget Sound in nearby Tacoma. And then came Zorn.

A few months after being the last training-camp cut of the Dallas Cowboys – he was originally told he'd made the team, only to get released two days before the opener because Dallas had traded for running back Preston Pearson – Zorn signed a $28,000 contract with one of the NFL's two new expansion teams. As the story goes, Zorn had already reached an unofficial agreement to join the Los Angeles Rams as soon as they could clear a roster spot, but after weeks went by without a contract, the Seahawks swept in and made the deal.

Zorn didn't know much about the city of Seattle, and he certainly didn't know anything about the new expansion team. In fact, the Seahawks didn't even have a head coach yet, as Jack Patera was still a few weeks away from signing on.

But Zorn quickly endeared himself to both the Seahawks and the city of Seattle. In the first preseason game of the inaugural 1976 season, he came off the bench and nearly rallied his team to a comeback win over the San Francisco 49ers. He scrambled 13 yards on the final play of the game, getting within two yards of the end zone before the Seahawks fell 27-20. A week later, Zorn replaced Neil Graff as the starting quarterback, a job he would keep when the regular season began.

While the Seahawks weren't exactly championship contenders during that first season – they went 2-12, with one of those victories coming against fellow expansion team Tampa Bay – they were definitely exciting.

"We won two games, but you'd thought we nearly went to the Super Bowl," Zorn said. "There was this grace period, where the coaches were getting to know each other, we were getting to know each other, and fans were getting used to having a team. It didn't matter what we did. It was just flat-out exciting."

Zorn's skill set led the coaching staff to design an unconventional offense that featured the "sprint draw." That system called for the quarterback and halfback to run along the line of scrimmage, parallel to each other, resulting in either a handoff or a rollout pass. On the running plays, Zorn would typically give halfback Sherman Smith the ball seven yards deep, then Smith would adjust to the defense. The offensive line employed a blocking scheme that called for the linemen to react to oncoming defenders, causing the defensive players to over-pursue by blocking them in the direction that they were already going. Smith would then look for a hole and turn upfield. On passing plays, Zorn would roll out with Smith, fake the handoff, then drop back and fire downfield.

The scheme had some success, mostly because of its uniqueness. But without a fleet-footed quarterback like Zorn, it had no chance.

"I do remember having this sense that what we were doing on offense was so deceptive that teams had a hard time stopping us offensively," Zorn recalled. "We threw for a lot of yardage; we ran for a lot of yardage. We just were very difficult to defend."

It wasn't until the franchise's third season that the offensive success started to translate to victories. Zorn led the team to 9-7 records in both 1978 and 1979, just missing out on the postseason both years.

"There were teams going to the playoffs and going to the Super Bowl, and all that kind of stuff, and we felt like we were competing as well for those goals," Zorn said. "We wouldn't have known that we were a ways away. We were playing like, at any moment, we could be in that game."

In the end, those two seasons turned out to be the heyday of Zorn's run as the starting quarterback. He remembers those two seasons more vividly than the others, and recalls one of the early victories of the 1978 season as a microcosm for how the little expansion team found a way to compete with the rest of the league.

With a little trickery, particularly on a key play late in the game, the Seahawks upset the Chicago Bears that year. Zorn doesn't remember much from that game, but he sure does recall that trick play at the end.

Seahawks vs. Chicago BearsNovember 5, 1978

as told by Jim ZornIt was one of those games where both teams were battling back and forth all day. Late in the fourth quarter, we were up 31-29. But the momentum was theirs. We had to get a first down to put the game away. It was late in the game, seven minutes to go. And there was a second-and-long.

We had practiced this play several times during the season. It kind of reminded me of the Boise State game in the 2007 Fiesta Bowl, where they had practiced certain plays during the year, and this was the game they had to use them all. Ours wasn't that severe, where we felt like we had to get into the bag of tricks and grab it all, but we did have this one play.

So here's what it was. I lined up behind the center, and Steve Largent was out to the right. We had a tight end to the left. We had two running backs. One of the running backs was Dan Doornink, and we lined him up at about eight yards.

I got up to the line of scrimmage, and I looked out. I had a little bit of an acting job. So I get behind the center, and I look out to Steve and act like Steve is doing something wrong.

So I go in motion, I'm walking now, away from the center, and I'm yelling Largent's name. I go: 'Largent! Largent!' And then I say, 'Hut!' I kind of give the other offensive players a feel for the rhythm: 'Largent ... Largent ... hut.' Then the center snaps the ball to Dan Doornink, and I block off the edge.

There was a blitz called, but everybody just kind of sat back because they thought I was going to call timeout. So the ball gets snapped to Doornink, he punts it, a quick kick. He punts the ball, Steve takes off and flies down the field.

Well, we were at midfield, and this punt goes end over end, end over end, and it rolls to the 1-yard line. And I thought it was going to go right through Steve's legs. He was standing at the goal line, turned around and facing us. But he just stuck his hands down quick enough and stuck the ball at the 1-yard line. And they ended up needing 99 yards for a touchdown.

We end up winning the game. That's a pretty significant play. I don't really remember anything else that happened in the game, but I do remember that play very well.

All they needed was a field goal, and we kept them away from it. When they made the call, I thought: What a great idea. The momentum was kind of shifting, and this particular play deflated their team. They couldn't get anything going after that. It was very much a deflation for their team. I just remember what an incredible play it was.

Trick plays became a staple of the Seahawks' early existence. The following year, in 1979, Zorn was involved in one of the most memorable plays in Monday Night Football history when he threw a pass on a fake field goal. Burly kicker Efren Herrera bobbled the ball before finally catching it for a 20-yard completion while causing MNF announcer Howard Cosell to say: "The Seahawks are going to give the nation a lesson in entertaining football."

In hindsight, Zorn looked back on those days as: "We had to do things like that to create the ability to compete with the other teams in the league. We had to be a little tricky."

But winning in the NFL also takes talent. And while the Seahawks had Zorn and Largent and later added defensive players like Jacob Green and Kenny Easley, they struggled to take the next step. They went 4-12 in 1980, 6-10 in 1981 and struggled to a 4-5 record in the strike-shortened 1982 season.

Along the way, Zorn suffered some serious injuries, including a broken ankle that would require a six-inch plate in 1982. He was never the same after that injury, and midway through the 1983 season he lost his job. The Seahawks were playing the Pittsburgh Steelers in an Oct. 23 game, and Zorn was struggling so badly that new head coach Chuck Knox benched him at halftime. Second-year player Dave Krieg came on in relief and rallied the Seahawks, falling just short of a comeback win. After that, it was Dave Krieg's team. Krieg helped lead the Seahawks to the AFC championship game that year, and Zorn had to settle for being a backup.

Not that it was easy.

"I got demoted, and we went to the playoffs. How good is that?" he said in 2007.

What got Zorn through the demotion was his Christianity. He professed to be a dedicated Christian when things were going well, so he told himself that he had to continue to be the same when times went bad.

"I found it very easy in my Christianity, because (positive) things were happening," Zorn said of his early years as a Seahawk. "Here I was, Big Man on Campus, the starting quarterback, everything was going well. It was easy.

[ Chris Goodenow · The Herald ]

"Now I was going to have to live out this reality. I just got demoted. I had to decide whether I was going to live out my profession of faith even in the bad times. So that's what I tried to do."

Zorn continued to support Krieg until 1984, when the team that gave him his first big break no longer had room for the crafty left-hander with the nimble feet. Zorn remembers driving into the parking lot of the Seahawks' complex in downtown Kirkland on an August morning. He knew it was Cutdown Day, but didn't really give much thought to his job security. Only when he saw special teams coach Rusty Tillman, the Seahawks' designated "Turk" in that he was the one who told players they had been cut, standing outside the complex did Zorn get an inkling that this Cutdown Day would be much different than previous ones.

"I thought: he's never standing outside waiting for guys," Zorn later recalled. "Little did I know, he was waiting for me."

After being with the Seahawks for the franchise's first nine seasons, Zorn had to find a new team and a new future. And, after the initial disappointment passed, he was fine with that.

"Being a backup player was a lot more difficult than being cut," Zorn said. "Being cut, you're free to go somewhere else to play. Being demoted, I had to be in there (the Seahawks' practice facility) every day."

Zorn ended up signing with the Green Bay Packers but saw limited playing time as a one-year backup there. He spent the 1986 season with the Winnipeg Blue Bombers of the Canadian Football League, then came back to the U.S. for one game with the Tampa Buccaneers during the 1987 strike. That would be his final game as an NFL player.

Zorn then approached Seahawks head coach Chuck Knox and inquired about a coaching job. Knox told Zorn that the crafty left-hander might one day become an NFL assistant, but that Zorn would have to go someplace else to find the first step on his path.

"Chuck Knox said: 'You have to go out and see if you can last in this profession, work your way up,'" Zorn recalled. "That really ticked me off. But it helped fuel that fire. It made me say: I don't want to be a good coach, I want to be a great coach."

Zorn ended up at Boise State University, where he coached the quarterbacks for four seasons. He went on to Utah State, and then to the University of Minnesota.

In 1997, he finally made it back to the NFL, and to Seattle, as a Seahawks assistant. But he spent just two years there before head coach Dennis Erickson and most of his staff were let go. After that, Zorn landed in Detroit, where he worked under head coach Bobby Ross with the Lions.

When Ross was fired in 2000, Zorn was again out of a job. He made a call to Seahawks coach Mike Holmgren, who welcomed the former legend back to town.

On Feb. 16, 2001, Jim Zorn was named quarterback coach of the Seattle Seahawks. Two weeks later, he was given his first major project when the team traded for untested quarterback Matt Hasselbeck and immediately named him the starter. Zorn worked closely with Hasselbeck in a relationship that had plenty of ups and downs.

[ The Herald ]

Zorn remembers one conversation after Hasselbeck had lost his starting job to Trent Dilfer in 2006. Hasselbeck told Zorn that he felt too confined in Holmgren's system. Zorn remembers telling him: "Good. That's your freedom."

"There were several turning points in his career," Zorn said after passing along that story, "and I think that was one of them."

Eventually, Hasselbeck not only got his job back but also became one of the best quarterbacks in the NFL. He helped lead the Seahawks to Super Bowl XL and went to multiple Pro Bowls.

"He's the guy I spent all my time with," Hasselbeck said during the pinnacle of his career as the Seahawks' quarterback. "I know for sure that he does not get the credit he deserves for that. It wasn't always fun, it wasn't always easy, and he rode me really hard when I first got here. But he's a great coach and a great offensive mind. We really get along really well now."

While Zorn took pride in Hasselbeck's rise to success, he experienced several other emotions as well during the historic run to Super Bowl XL. As the quarterback who started it all, Zorn basked in the glory of seeing the Seahawks make it to the ultimate game.

"What I enjoyed was that all the older guys, guys that I had played with, they were as excited as I was," Zorn said. "For me, it was even more of a joy because I was on the inside. I got to go to all the meetings. I got to be there and experience it. But there were a lot of others (outside of the locker room) that were able to experience it with us."

And as for his 1976 notion that the expansion Seahawks were not that far away from the Super Bowl?

"What I know now, after going to the Super Bowl in 2005, is that it's really hard to get there," he said more than 30 years after playing in his first game as a Seahawk. "It's really hard -- a lot harder than we thought back then."

In 2008, Zorn took on an entirely new challenge after being named head coach of the Washington Redskins, a stint that lasted two years. In 2011, he is back coaching quarterbacks with the Kansas City Chiefs. Those who remember Zorn's early days as quarterback of a fledgling franchise know that he's up for just about any challenge put in front of him.