While John L. Williams was a wishbone tailback at Palatka High School in Palatka, Fla., no one would have guessed that he would develop into one of the best three-dimensional backs in NFL history. He had plenty of opportunities to run the ball in high school, but rarely was he asked to block anyone or catch a pass out of the backfield.

"In four years of high school," Williams mused, "I probably caught 20 passes."

During his days as a fullback for the Seattle Seahawks, Williams was known to catch that many passes in the span of two games.

As he once promised fellow dual-threat running backs Thurman Thomas and Roger Craig during the week leading up to one of his two Pro Bowl appearances, Williams found a way to do things that few other runners had ever done. During a 10-year career he caught 546 passes, which marked the second-most receptions by an NFL running back when he retired in 1995.

But when the Seahawks found themselves trying to keep their heads above water during the 1988 season, it was Williams' running that helped propel Seattle into what would be their final postseason appearance in more than a decade.

John L. Williams did a lot of things well during his storied NFL career. Running is what he did better than anything else.

Who needs organized football?

That's what John L. Williams thought during a childhood that included hours upon hours of street ball played with neighborhood friends. Williams, who typically played quarterback in the unofficial games that went on in his Palatka, Fla., neighborhood, couldn't imagine anything better than drawing a play in the dirt and free-lancing his way to a long touchdown scramble.

But in ninth grade, the playground moves finally crossed over to a 100-yard field with lines and referees. Williams decided to go out for the football team, only to find out that it might not be the smooth transition he expected.

"They wouldn't let me play quarterback because I was too big, so I had to play line," said Williams, who was a sturdy 175-pounder in ninth grade. "I told them I didn't want to play line, and they said, 'Well, that's what you have to play.' So I said, 'I'm quitting.'"

Fortunately for Palatka High School – not to mention the hundreds of college and NFL teammates Williams would have over the years – he came back two days later and offered to play running back. The coaching staff wisely accepted the deal.

Williams starred on the freshman team his first year, making such an impression that he was called up to varsity for the final two games. He played the entire fourth quarter of the season finale, and the writing was on the wall for Palatka's future. Over the next three years, Williams was the starting tailback and was named to Parade's All-America team as a senior.

He made visits to Miami and Auburn but canceled a scheduled trip to USC – also known as Tailback U. – because of a fear of flying. Williams had never been on a jumbo jet, and when a Michigan plane crash dominated the news a few days before his scheduled departure for L.A., Williams blew off the Trojans.

"That was it," he recalled. "I couldn't get on a plane after I saw that. That stopped my trip right there."

Williams, by then a 215-pound tailback, opted instead to attend the University of Florida, which was just a 30-minute drive away in Gainesville. Offensive coordinator Mike Shanahan recruited him, seeing the potential of a running back who could catch the ball out of the backfield.

"He could just do it all," recalled Shanahan, who went on to become head coach of the Super Bowl champion Denver Broncos and now the Washington Redskins. "He could catch the ball. He didn't have to catch a lot of passes, but you could see that he could catch it. He was a great all-around player."

Much as he had during his his prep career, Williams made an immediate impression at Florida. He split practice time with fellow freshman Neal Anderson and sophomore Lorenzo Hampton leading up to the season opener, and performed so well that the coaches were prepared to let him start at tailback. But a hamstring injury set him back before the first game, and Anderson took over as starter.

"Neal came in, and from that point on he was getting 200, 300 yards a game," Williams said. "So when I came back, I didn't want to alternate at tailback."

And so Williams offered to switch to fullback, where only senior James Jones stood in his way of being a starter. Williams split time with Jones as a freshman, showing surprisingly good hands for a fullback who had played in a running system during his high school days.

Williams started as a sophomore and helped the Florida Gators go 27-4-3 over the next three seasons. While Anderson and Hampton carried the load as tailbacks, Williams helped their cause with punishing blocks. He also got enough opportunities running the ball to pile up 2,409 rushing yards. And Williams proved, as Shanahan had predicted while recruiting him in 1981, that he could catch passes. His 92 career receptions were a Florida school record for running backs. In one game during his senior season, Williams caught 12 passes against the University of Georgia – or more than half the receptions he had during his entire high school career.

But without a single 1,000-yard rushing season – his best year saw him go for 793 yards on the ground -- Williams was not regarded as a feature back in the NFL. He was initially viewed as no better than a third-round pick in the 1986 draft, and some scouting services were projecting him as a fifth rounder.

Not until the February scouting combine did the scouts begin envisioning a mold-breaking fullback who might blossom into an NFL star because of his versatility. During that combine for pro scouts, Williams blew away the competition in several drills. Competing against fullbacks and tailbacks, Williams put on quite a show. He finished first in a quickness drill, ahead of future No. 1 overall pick Bo Jackson, and also took second behind Anderson, his former teammate, in the 40-yard dash. (Jackson did not compete in the 40 that year.)

Williams was so impressive at the combine that teams began trying to move up in the first round to land him. According to Williams, the Los Angeles Raiders, Cleveland Browns and Kansas City Chiefs all tried in vain to improve their first-round pick and get a shot at the quick fullback with the soft hands.

But the Seahawks beat them all to the punch, nabbing Williams at No. 15 overall – 12 spots ahead of his old pal Anderson. (The previous year, another Gator went No. 27 overall when Hampton was picked by the Miami Dolphins.)

The first thing Williams noticed upon joining the Seahawks was that the starting tailback was a pretty good guy. And quite a player. Williams was excited to block for Curt Warner, just as he had for Anderson at Florida.

"We bonded right away," Williams recalled. "Curt was the man. I knew it was going to be a good running game. The only thing (Warner's presence) could do was help the running game. I knew I was going to block but also catch a few balls. I caught quite a few passes."

Williams caught 33 passes as a rookie, 38 as a second-year player, and 58 in his third season. He was not only putting up impressive stats, but Williams was also becoming a big-game star. His 75-yard touchdown reception on a screen pass helped beat the Chicago Bears in 1987, clinching a postseason berth. In October 1988, he helped overcome the loss of injured quarterback Dave Krieg by scoring three touchdowns in a win over Atlanta.

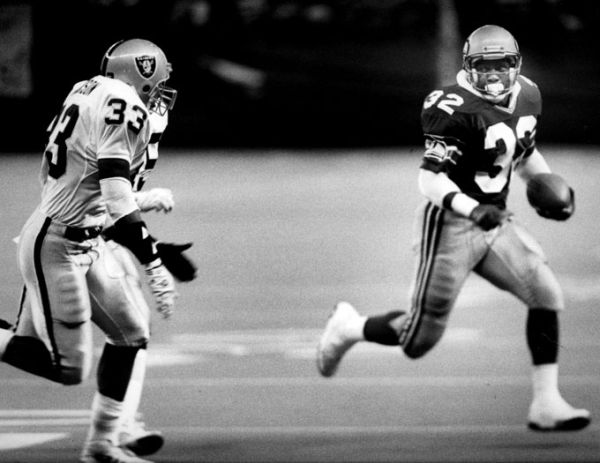

But it wasn't until the final month of that 1988 season, when the Seahawks were hovering around the middle of the AFC pack, that Williams really turned it on. Thanks in large part to Williams' play, the Seahawks won three of their final four games and took home their first AFC West title. The first of those four games came against the rival Raiders, and the sure-handed Williams used his legs to help record a historical first in franchise history.

Los Angeles Raiders vs. SeahawksNovember 28, 1988

as told by John L. WilliamsIt was Thanksgiving weekend, 1988, and we were getting pretty desperate for a win. We had just lost to Kansas City to fall to 6-6, and the playoffs were looking like a long shot. We knew that if we could win out, we had a chance.

We were in the AFC West, and there were some tough teams in that division. If you didn't win 10 ballgames, you were probably not going to make the playoffs. Back then, we had the division champion come out of there, and then we had two or three other teams fighting for a wild-card spot. It took 10 or 11 wins just to get a wild-card spot; it was such a good division at that time.

Of course, the Raiders were always in the mix. And it was the same that year. Any game we played against the Raiders, it was something special. For some reason, that was the game for the Seahawks to play. Our fans always looked forward to that game. And of course, Chuck Knox was one of those guys who really wanted to beat those guys. He would have given anything in the world to go out there and beat them.

It was also Monday night. What Coach Knox would always say is that it's the only game on TV that night, so you've got everybody in America watching. So whatever you do, you go out there and do your best because everyone in America's watching. Usually, on Sundays, there are other games being played. But on Monday night, we were the only game on. He always emphasized for us to fare well on national television.

We didn't have very many Monday night games at home, but we always had one against the Raiders. So you knew it was going to be a big game. There was so much excitement because the game started in the evening. You had to prepare for the traffic and all that. So Chuck Knox had everything planned out for us. And we always looked forward to it.

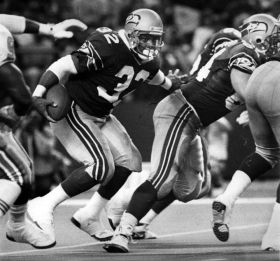

The plan was to run the ball, which was no secret. Every game was that way with Ground Chuck. For some reason, that game the offensive line was blocking particularly well. It didn't matter who touched the ball. They were blocking so well that it didn't matter whether me or Curt got ball. It was typical Ground Chuck.

I could tell in the first half, actually, that we were going to run at will. Curt was running up and down the field. It was just one of those games where he was on a roll and they couldn't stop him. He had 61 yards by halftime, and we were up 21-20. I was having a pretty good game, too, with 67 rushing yards on just eight carries at the half.

At that time, most teams tried to stop Curt Warner first in the running game and stop me in the short passing game. That day, we didn't need to pass at all. And Curt got tired. So I carried the ball at the fullback position, or they took Curt out and I carried the ball from the tailback position.

We started to pull away in the fourth quarter, although it got a little interesting. But we ran the ball at will, and of course we had to get Steve Largent a pass in there. We had to give him a ball or two every game.

We ended up winning 35-27, with Curt gaining 130 rushing yards and me adding 105. It was the first time in franchise history that two Seahawks runners went over 100 yards in the same game, and it couldn't have come at a better time.

That particular win definitely made a difference. We were on a roll. We beat the Raiders, and we knew then that we had a chance in our next three ballgames to win. We knew we had a chance for the playoffs.

As it turned out, the Seahawks did make the playoffs that year, winning the AFC West despite a 9-7 record. And Williams' contributions did not stop with the Thanksgiving win over the Raiders.

Two weeks later, in a one-sided win over Denver, Williams and Warner each went over 100 rushing yards again. That gave Seattle an 8-7 record and sole possession of first place in the division.

For the regular-season finale, the Seahawks had to face the Raiders again, this time in Los Angeles. Whereas the Raiders held Warner to just 21 rushing yards on 10 carries, Williams broke their backs again by accounting for 239 total yards of offense, including 180 in receptions. The Seahawks had won their first AFC West title and earned the right to face the Cincinnati Bengals in a divisional playoff game.

Cincinnati had an interesting game plan that week, but it worked out in the end. According to Williams, several Bengals defenders told him: "John, we're going to let you catch your passes. But the rest of the team is going to have to beat us."

Williams caught his passes – an NFL playoff record of 11 in that game – but his teammates couldn't hold up their end of the deal. Cincinnati ended up winning 21-13 in what would be Williams' final playoff game as a Seattle Seahawk.

He ended up going to back-to-back Pro Bowls in 1990 and 1991, and it was during the week of that annual all-star game that Williams had a pivotal conversation with two other dual threats. Williams got together with Buffalo's Thurman Thomas and San Francisco's Roger Craig and discussed the importance of revolutionizing the running back position. All three players had thrived as threats in both the running game and the passing attack, and so Williams realized for the first time that he might have made a significant impact on the sport.

After the playoff loss to Cincinnati, Williams spent five more years in a Seahawks uniform while the team went through a transitional stage. Warner and Largent retired, Knox was fired, and several other key components left town. So by the time Williams became a free agent in 1993 he was ready to move on himself. Citing a desire to play for a winning team, Williams signed with the Pittsburgh Steelers.

And win he did. The Steelers went 12-4 in 1994, falling just short of the Super Bowl when the San Diego Chargers shocked them at home in the AFC Championship game.

"It was supposed to be minus-20 degrees in Pittsburgh," Williams recalled. "But the day that we played San Diego, it was 67 degrees.

"We were so good that year that we had started to make reservations for the Super Bowl down in Miami. But that Sunday came, it was 67 degrees in Pittsburgh, and they ended up beating us -- wow."

The next year – Williams' final season in the NFL – he made it to the pinnacle of his sport. Williams and the Steelers went to Super Bowl XXX that season before losing to the Dallas Cowboys in what would become the final football game of his storied career.

"Ten years in the league, running on (artificial turf), it just caught up with me," he recalled in 2007, looking back on the physical effects that eventually limited his production.

His retirement came without much fanfare, and yet one of the game's true pioneers had left the league. Not until years later would people really appreciate what Williams, Thomas and Craig had done for the position. While the 1970s and early '80s featured one-dimensional runners like O.J. Simpson, Walter Payton and Eric Dickerson, the new NFL started looking for more dual threats. Williams's success as a receiver out of the backfield helped opened the door not only for fleet-footed fullbacks like Christian Okoye, Larry Centers and Mike Alstott, but also for combination tailbacks like Marshall Faulk, Tiki Barber and LaDainian Tomlinson.

With so few running backs able to thrive as runners and receivers, the sport got more and more specialized over time.

"If I'd been playing now," Williams joked with modesty in 2007, "they'd have a guy to come in and block on running plays on first down, someone else to catch a pass on second down, and someone else to come in and block on pass plays on third down. I probably wouldn't even be playing now."

While he finished his career in Pittsburgh, Williams never forgot where he got his NFL start.

"Seattle gave me an opportunity," he said. "They gave me a chance."

Williams eventually moved back to his home state of Florida, opening a night club called John L's Club Remy. He owned the club for six years before deciding to sell.

"Anytime you've got liquor," he recalled, "you've got the fighting and all the bad things that go with it. It was fun, though."

In 2005, he joined former UF teammate Kerwin Bell as an assistant coach at Ocala Trinity Catholic High School. He kept his job in 2006, when another former Gator, Ricky Nattiel, took over as head coach. Williams was enjoying his tenure as running backs coach, but he admitted that it was sometimes tougher than playing. For someone as talented as Williams, teaching a running back to catch passes isn't as easy as just going out and catching the passes yourself.

"The receiving part is more natural," he said. "When somebody runs a pattern, and you throw it, you can tell if he's a pass catcher."

Williams, who was a true pioneer in terms of redefining the fullback position, proved for a long time that he was a natural pass catcher.

"He was definitely an inspiration to me," said future Seahawks fullback Mack Strong. "... He was a guy who was very versatile. He could run, he could block, he could catch. He did some great things to help him have a very successful career.

"When you think about great backs who were receivers, you think about him, you think about Roger Craig, you think about Larry Centers. Those are some of the guys who stood out to me that you could count on at any time."